A young woman turns to Holmes for protection when she's menaced by an escaped killer seeking missing treasure. However, when the woman is kidnapped, Holmes and Watson must penetrate the city's criminal underworld to find her.

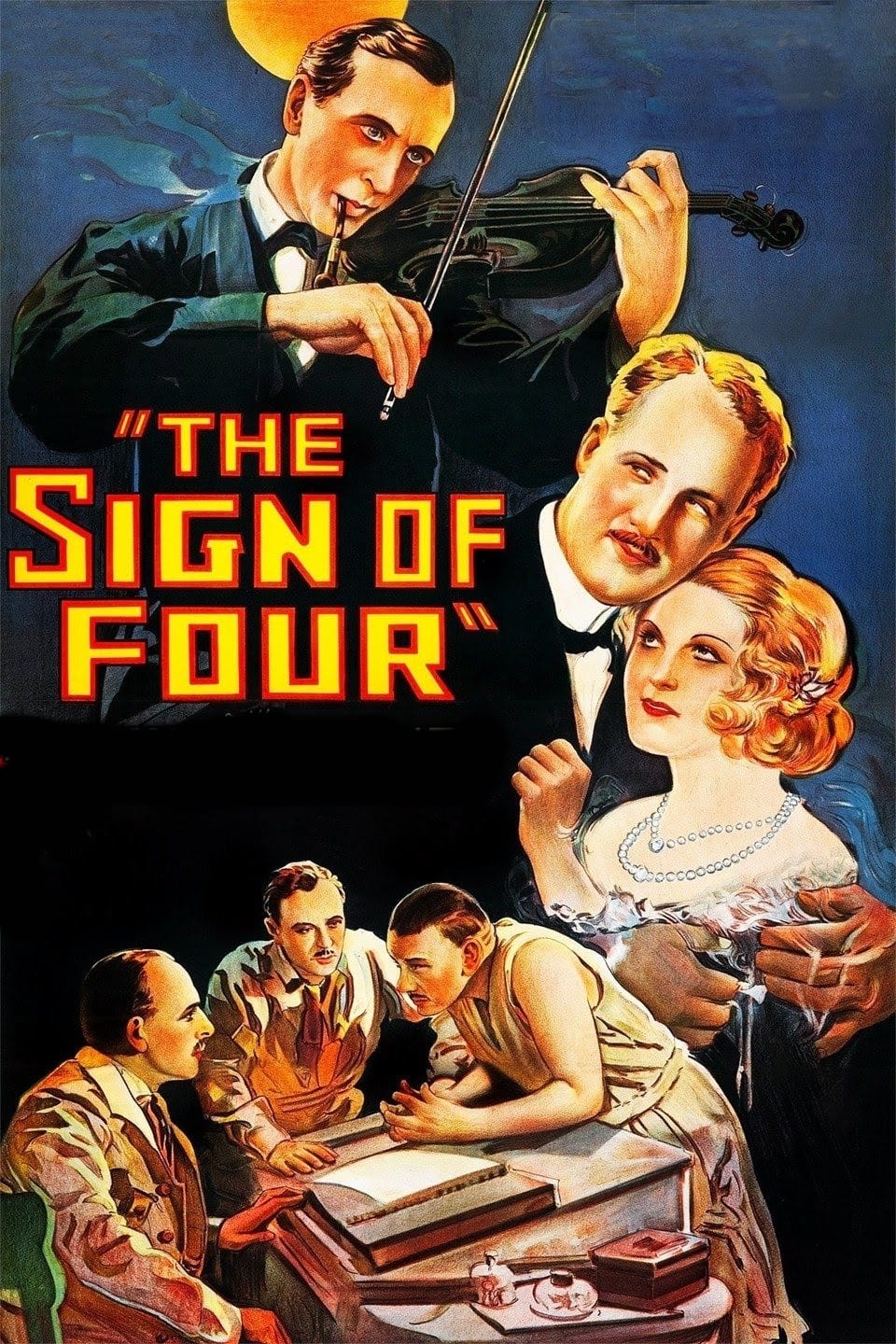

06 Dec The Sign of Four: Sherlock Holmes’ Greatest Case (1932)

Displaced Mind and Eye

The form — at least as established in the Holmes stories and subsequent early detective fiction, has the reader experience things in the order the detective does. In the best, there is some tension as we know the detective is ahead of us in deducing the truth from the same information we have. If you deviate from this, there should be some value because the cost is relatively high.

Now here we have one of the earliest experiments with detective talkies and they went directly to Holmes. What they did here was break the rule in an odd and experimental way. All the history that we are supposed to discover is presented before we even meet Holmes. That is, the story is presented in the historical order of events instead of the order of discovery.

I cannot know the effect this had on the audience when it was new. This film is far closer to when the Holmes stories appeared than it is to me here now. But my guess is that it failed.

There is another experiment, and pretty interesting. Two scenes are shot from high. One of these has an established human perspective: Holmes climbs up a ladder and when he comes down, the camera stays there looking down. Later, when the big chase/fight climax is going on, we again have the camera at this angle — a little further away. The effect must have been striking to the contemporary audience.

These two decisions are at least consistent: we don’t see things the way our detective does.

Posted in 2015

Ted’s Evaluation — 3 of 3: Worth watching.

No Comments