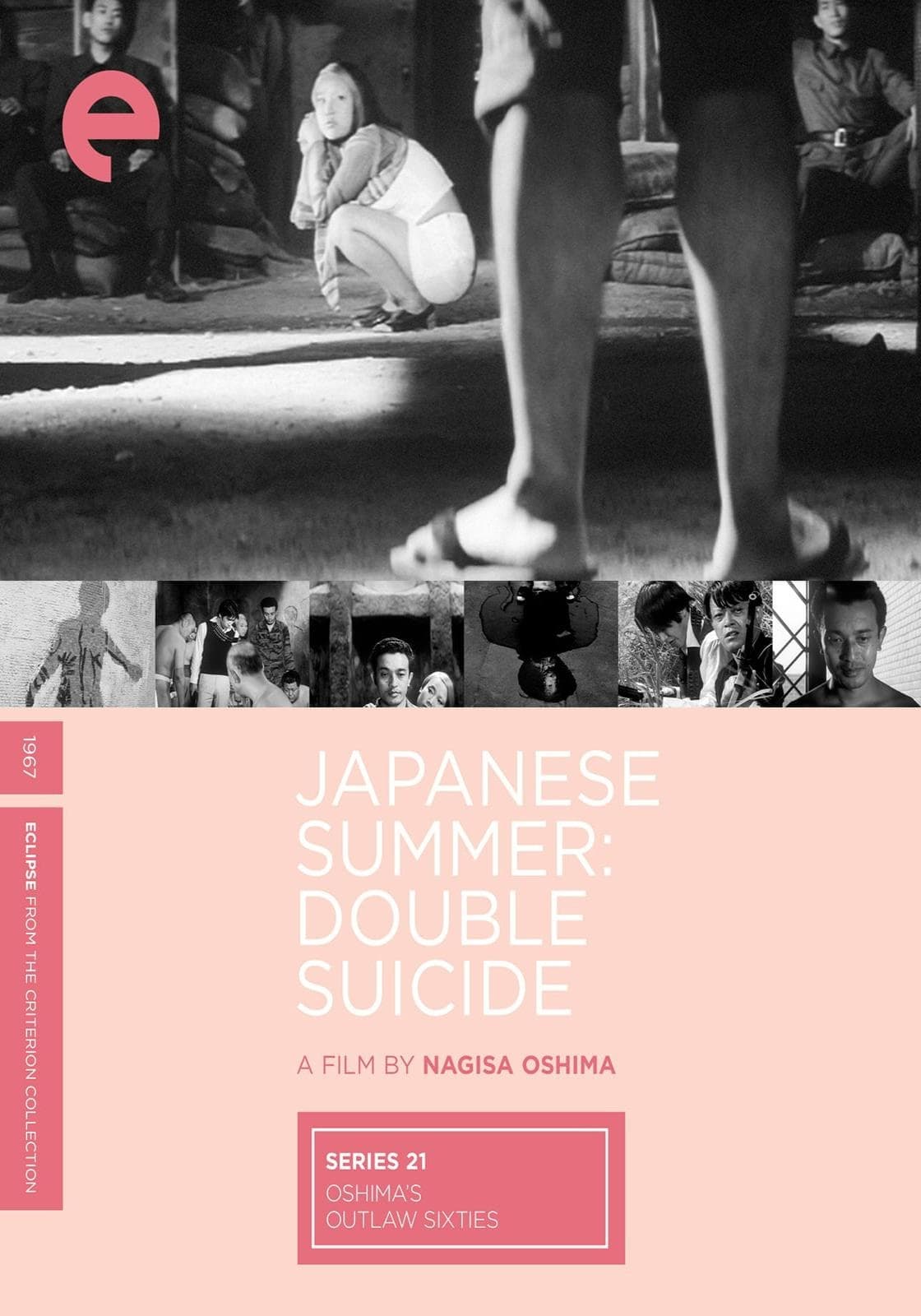

A sex-obsessed young woman, a suicidal young man she meets on the street, a gun-crazy wannabe gangster—these are just three of the irrational, oddball anarchists trapped in an underground hideaway in Oshima’s devilish, absurdist portrait of what he deemed the “death drive” in Japanese youth culture.

13 May Japanese Summer: Double Suicide (1967)

Solid Shadows with Death Wishes

I know a few of this man’s films. They are among the richest experiences I know, but I was surprised at how deeply this one worked on me.

The surprise comes in part from knowing how specific his target audience was. I am the right generation but the wrong decade and culture. I recently encountered the effect with “Naisu no mori” which took some significant shifting on my part to put me in the right place.

Oshima is politically radical, violently iconoclastic and deeply critical of what he sees as a broken Japanese culture. In this film he targets sensibilities that would be hard for even Japanese viewers to understand today. I didn’t even try, and simply relegated all the broken souls I saw to a generalised brokenness. Perhaps that makes the film better, because it allows us to experience the technique of the thing more directly.

The story doesn’t matter except that it throws an eighteen year old girl with a “screw loose” in with a suicidal AWOL soldier and a group of ragtag gangsters. Some of the action takes place in an abandoned futuristic city, but the core of the film is in a bunker of some sort. It is a terrific set and one wonders how in the world many of the shots were made. Some of them pan the space, showing walls that could not have been there at the start of the shot.

It is a complex space, concrete, with sometimes deep, sometimes close walls that seem to change. The floors and ceilings have different heights. There are stone altar slabs with spring water coming from roughly hewn holes. Sometimes the walls and floors have hand-carved human-shaped niches. The lighting always seems natural but the sources would be physically impossible. The space reminded me of Tarkovsky.

Oshima says he hates Ozu and Kurosawa, but the cameras of both clearly are used and extended here. The poses are formal, the movements of the eye are architectural. This film was unknown to me until today, and it replaces Welles’ Othello as my go to example of an architectural film. The characters are less people than they are active components of the space. Every action, every perception — ours and theirs — is spatially situated. I loved it. Mind you, this is in spite of missing the social commentary; some would think it was if I were watching a mimed Shakespearean play. But I think this film is in the eye, the space.

It is so extraordinary that I am giving it one of my coveted 4 ratings.

Posted in 2010

Ted’s Evaluation — 4 of 3: Every cineliterate person should experience this.

No Comments