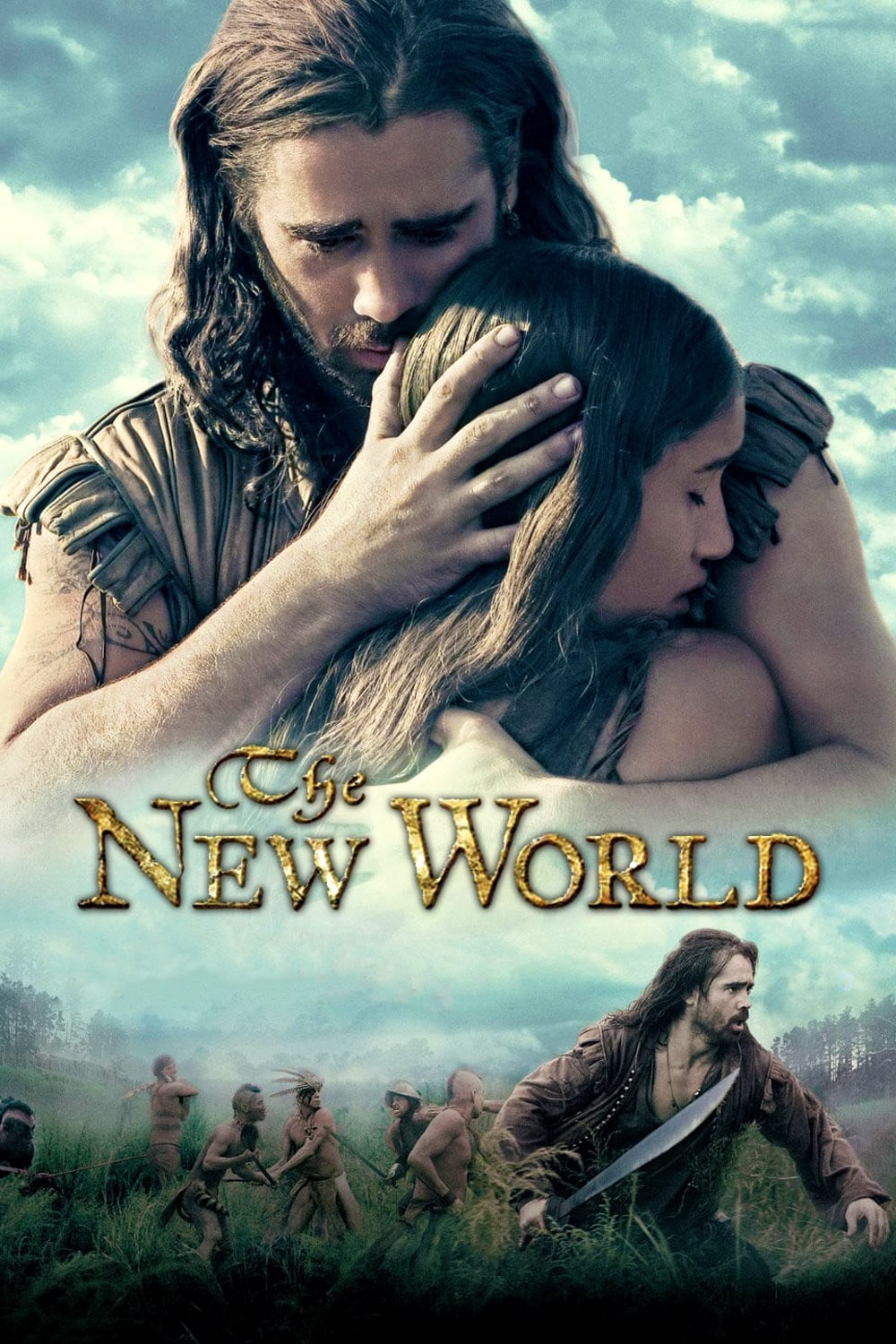

A drama about explorer John Smith and the clash between Native Americans and English settlers in the 17th century.

06 Aug The New World (2005)

Matoaka’s Miranda

(This comment was deleted by IMDb based on an abuse report filed by another user, because of some perceived religious slight.)

Malick’s method is to frame films as remembrances. Remembrances of romantic notions, whether freedom, peace, war or love (as his four films trace). This way, he can exploit a languorous floating through remembered reality that never is that gentle or considered in actual reality. He can use his narration as things remembered, floating over the sights. To make this as effective as possible, he plays all sorts of tricks with the sound, having different boundaries of different types between what you see and hear.

Added to this is a considered approach to framing. You may have noticed that most filmmakers stage the action as if the world arranged itself to fit nicely in the window the camera sees. It makes for nice pictures and clear, precise drama, but we know it for what it is, a theatrical device. Malick is like Tarkovsky; he likes to discover things and if the way the world frames things so that they are off the window we see, so be it.

That’s why his battle scenes are unique. With most directors, you’ll have smiting and dying nicely so that we can see it. Or alternatively, we’ll have point of view shots that are hectic as if we were a participant. These two battle scenes have the camera as a disembodied eye that shifts about as if it were the eye of dreams, or nearly lucid recalling or even retrospective invention. Sometimes hectic as if it were point of view, but never looking at what a combatant would, instead having a poetic avoidance.

I first met Malick when he was a lecturer at MIT and I a philosophy student. He spoke of French Objectivism, and was clearly bothered by how the notation and language constrained the ideas. At the time, I was doing my thesis on Thomas Harriot, who is the hidden motivator behind everything in this story — the real story. Malick never saw the thesis because by the time it was finished, he was off to explore this business of experiencing from the “outside” in cinematic language.

But Harriot is likely the inventor of the “external viewer of self” notions that Malick liked (as they reappeared in the French ’60s) and uses in his philosophy of film. Harriot suggested he got it from the Chesapeake Indians. So the circle closes: a film about a people using their own mystical memory-visions.

If you take a little time to tune yourself to Malick’s channel, you will find his work to be transcendent. I consider this one of the best films of 2005, despite its apparent commercial gloss and the mistaken notion that most will have that it is a love story. It is about remembering and inventing love in retrospect. A world is always new so long as the imagination of recall is supple.

The rest of this comment is of an historical nature. The love story is made up of course, but that’s apt for a movie that is about invented memory. The Indians are mostly wrong, the body paint, hair and dress; according to the only document we have, the John White paintings, men and women were mostly nude even in winter and prided themselves on tolerance to the cold. There is no mention of the famous local hallucinogen, cypress puccoon which was widely traded and how a stone age people were able to survive in a land a hundred miles from the nearest stone.

(My original comment was deleted, presumably because there was a note about the unpeaceful nature of the people. Readers may want to consult good histories for that.)

Harriot (a scientist and mage) wintered over with a nearby “holy” tribe in 1585, and after he left, Powhatan destroyed the tribe lest they combine their magic with Harriot’s and overcome his stranglehold on taxes. He married the wives of the chiefs he murdered. Matoaka (Pocahontas) was almost surely the offspring of this union and it is why he sent her as a naked 10 year old to negotiate with the Jamestown settlers, who Powhatan thought was Harriot returning.

Powhatan never exiled Matoaka. When negotiations with the settlers failed, he married her off to a satrap in the north to expand his empire. From there she was kidnapped. When he knew that Rolfe had shamelessly promoted his marriage to an Indian princess and arranged an audience with the King, Powhatan sent the two holy men to accompany and protect her, those you see here. She presented to James, her father’s cloak that is also shown in the movie. It was designed by Harriot for the his host, the husband of Matoaka’s mother.

The scenery is very accurate and was filmed where things actually happened and in a few spots within a few hundred yards of where Harriot wintered over (and I now reside).

The Harriot/Matoaka story is a key source for Shakespeare’s “The Tempest,” and it is likely that Shakespeare actually met Matoaka when she visited Harriot. One of the accompanying Indian priests had an argument over God with a Nixon-like cleric who subsequently published a list of all the demons thus mentioned. You can see that list of demons appearing throughout “King Lear.”

Viewers interested in racial matters may be interested to know that by the time of these events, Spain and Portugal had already imported over a half a million African slaves to South and Central America.

I had marked this as a Four, but Malick has two others that trump this cinematically. But see this.

Posted in 2006

Ted’s Evaluation — 3 of 3: Worth watching.

No Comments