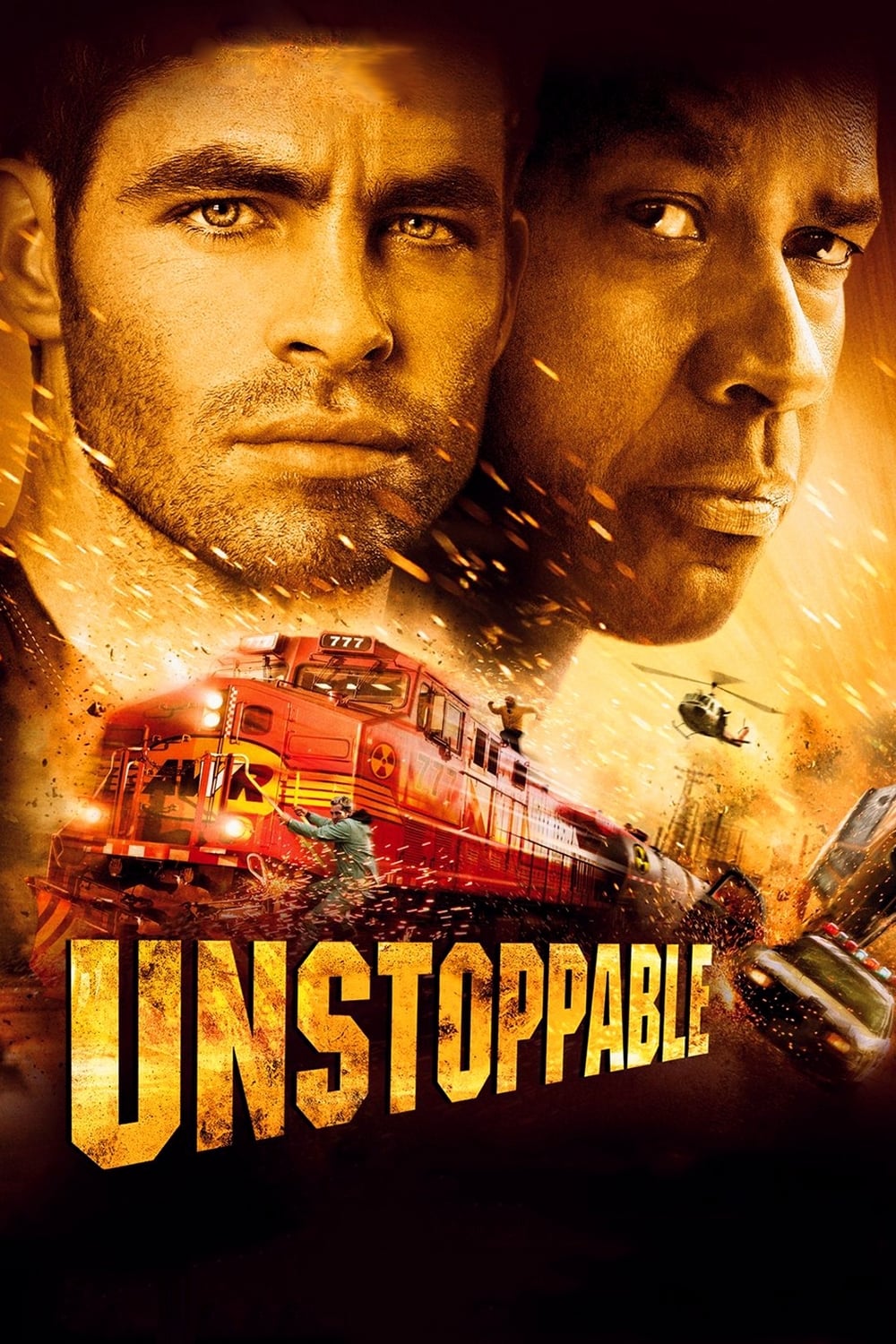

A runaway train, transporting deadly, toxic chemicals, is barreling down on Stanton, Pennsylvania, and proves to be unstoppable until a veteran engineer and young conductor risk their lives to try and stop it with a switch engine.

23 Feb Unstoppable (2010)

Unmovable Tracks

If we cannot get movies that matter, at least we can get movies that engage, and this one does.

This one does, and I think there are three devices consciously used.

One is plainly obvious, the cinematic energy that Scott knows how to deliver. There are thousands of small decisions that he and his team made. This is not just loud motion, but a breathing being with electric life. I am sure that there is no single thing here that is particularly novel, but his use of the cinematic vocabulary toward a single end, a small effective focus, is remarkable.

There is a similar shape to the story. Usually what we want to have is a human story, but because human emotions are uncinematic we place them in some larger visible context, perhaps a war. Then the flows of that larger scope can be shown and are inherited by the human level. This has been done thousands of times, effectively. Here we have the inverse: the story is about the beast, and we are able to anthropomorphize by inheritance from the human drama of a guy and problems with his wife that are outlined.

Even Scott‘s standard trick of locating us is used in the service of this device. What he loves to do is locate a scene for the viewer by giving a tickertape text (complete with tickertape noise) on the screen, so we know we are at the Scranton Curve. It is a cheat, a substitute for what should normally be done cinematically. He does it so he doesn’t have to waste any beats resituating us. But look what he does; for the whole film this is used for situation, until the very end. Then he uses a similar device, complete with font, to resituate the people, not the location. Clever.

But the big trick is one I comment on incessantly. A way to engage an audience is to place an audience in the movie and make them behave the way you want the viewers to. It is the visual equivalent of the laugh track, and exploits the science of mirror neurons. Scott‘s films have increasingly used this. Here, what we have is news crews bring the story to an audience we see as deeply engaged. Though the pending disaster will kill anyone nearby, the people flock to the scene.

Video from the TeeVee merges seamlessly with film footage. Helo shots from Scott‘s enterprise merge with this we see from the on screen helo. We know that the camera on the helo we see is interchangeable with the one we don’t. As the tension in the on screen audience increases, and their lives are at risk, we become similarly invested. Folding.

An incidental observation. For a hundred years, technology was a visual cinematic quality. Technology was big and better technology was bigger. Bigger steamships, bigger trains. Even bigger buildings were seen as technology, and would have been seen so by, say, the ‘King Kong‘ audience. Now of course, we live in a different setting, one in which more advanced technology is more microscopic and diffuse in ‘the cloud.‘

The train is no longer an automatic semiotic token for technology. For us and Scott, it is simply a big machine that is a mess, like the big corporations that are a similar runaway mess. The meaning has shifted, resituated.

Denzel, a problematic actor, is used well by Scott.

Posted in 2010

Ted’s Evaluation — 3 of 3: Worth watching.

No Comments