Actress Jane Wilkinson wants a divorce, but her husband, Lord Edgware, refuses. She convinces Hercule Poirot to use his famed tact and logic to make her case. Lord Edgware turns up murdered, a well-placed knife wound at the base of his neck. It will take the precise Poirot to sort out the lies from the alibis - and find the criminal before another victim dies.

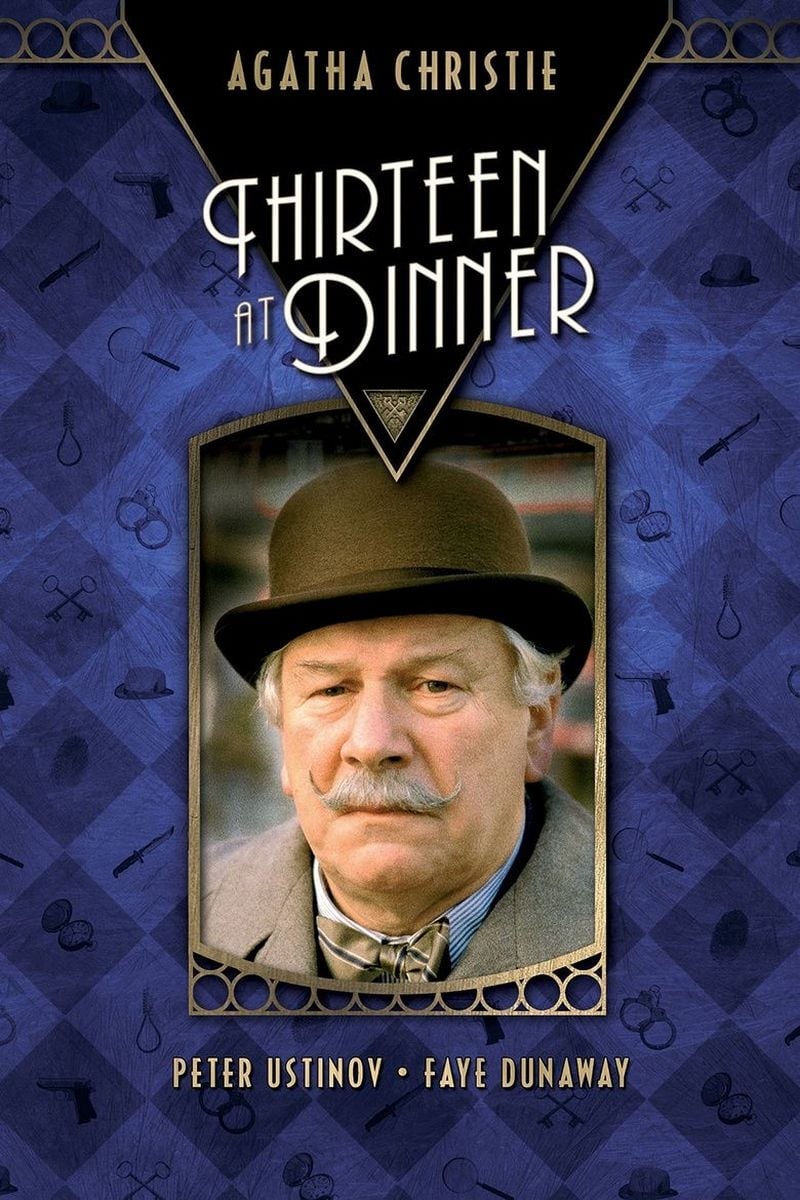

26 Nov Thirteen at Dinner (1985)

Suchet Sachet Suffers

A new batch of old TeeVee Christie adaptations have become available on DVD. I’ve been marching through them valiantly, looking for anything of value. Here it is. This one is good.

The story on which it is based is one of Christie’s more interesting experiments in playing with the mystery form: moving the narrative structure from one untrusted device to another. These sorts of narrative folds are challenging for filmmakers, which is why I movie versions of Agatha sleight of hand.

Here, the adapters did something clever in changing the whole focus of the story from the dinner in question to the surrounding lives of the actors (and the aristocrats, same thing). If you ignore the generally cheesy production values, you’ll be faced with one of the best Christie film adaptations I know.

But the real gem is Ustinov’s Poirot. Now I know I am in the minority here, but I find his Poirot the most satisfying. Its a tricky thing, making these evaluations, but the reason why has to do with his relationship to the process of discovery. With Marple, the process is a matter of already knowing what needs to be known about why things occur. All she has to do is match the circumstances she finds with what patterns she has stored.

Poirot is a different sort. He is engaged in a genuine battle with evil, an obsession which he camouflages as a way to address boredom. His method is closer to the Sherlock model, reasoning from cause; following paths and possibilities. When you travel with a real Poirot, you are always living in the future, many speculative futures mapped onto data from the past to extend cause. So the second murder in a Poirot mystery is always preventable, but for his openness to too many possibilities. He then punishes himself, resulting in his most characteristic personality traits.

TeeVee has taken the detective in a different direction. The engagement in the mystery is simply to present a series of baffling scenes and then explain them at the end. Along the way, you have to be, well, “entertained.” So they create characters to do so. In the books, the humor was laid on top of the detective spine. Its because though Christie was a great plot designer, she was poor when it came to wordsmithery. She made up for this by creating engaging characters. The formula is reversed in TeeVee. That’s why you have Suchet’s Poirot, and Brett’s Holmes. Their twitching and poking makes them amusing regardless of what happens around them. Ustinov creates a Poirot more in the spirit of one engaged with the narrative, and inspired by the drive to deduce.

The bonus here is that his foil is on screen, Inspector Japp. Japp plays a different role in the detection than Holmes’ Lestrade. He is competent, but limited in the ability to live in the future. He is, in fact, a junior Poirot. Here he is played by the very David Suchet who would become the much admired Poirot in a later series. His mannerisms are apparent here and distracting.

Posted in 2009

Ted’s Evaluation — 2 of 3: Has some interesting elements.

No Comments