A story within a story within a story. In Australia's Northern Territory, an Aboriginal narrator tells a story about his ancestors on a goose hunt. A youngster on the hunt is being tempted to adultery with his elder brother's wife, so an elder tells him a story from the mythical past about how evil can slip in and cause havoc unless prevented by virtue according to customary tribal law.

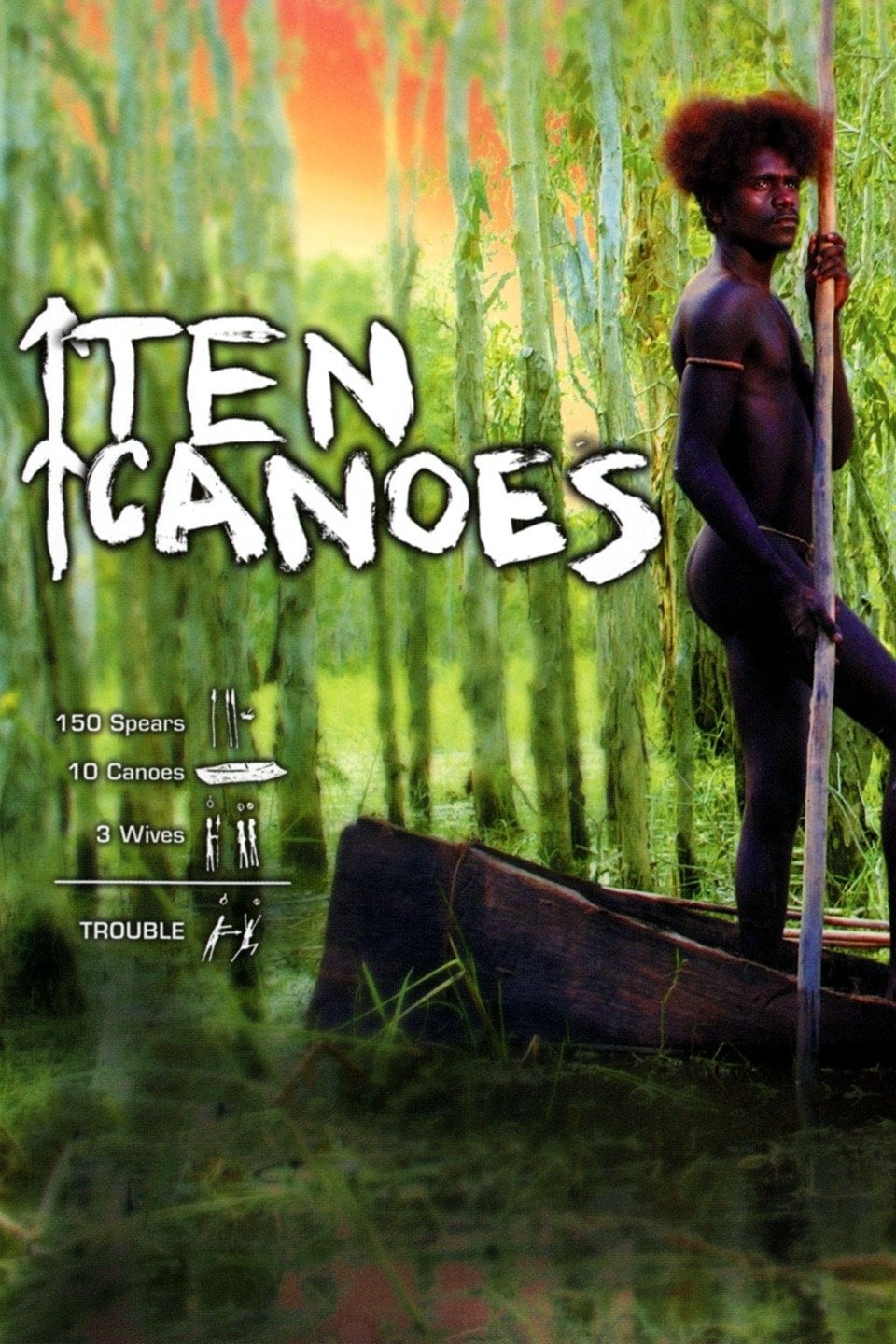

25 Nov Ten Canoes (2009)

Yolngu Goose-eggs

Sometimes all you need is magic. At least it seems so, when you see the real thing. If you happened to see Baz Luhmann’s ‘Australia’ and was confused, see this instead. It is the genuine article, about the magic, told with magic. It is circular, nested and webbed. It floats, and if you let it you will nearly be lost.

The cinematography here — all the cinematic values — are only slightly apparent and when they declare themselves, it is in the service of the story: switching from subdued colour to bright to signal the shift of what story you are in. Otherwise, the camera is either in conventional documentary mode or in space following spirits across landscapes as they voyage from waterhole python ouroboros and back.

What we have here is good old oral storytelling supplemented by image, and highly structured. Essentially everything is told by an offscreen aboriginal narrator, whose convoluted beginning establishes all sorts of narrative pockets that are revisited later. The story is a tree, we are told and in its telling we visit many branches. There is a sort of beginning, but it is nearly too complicated to describe. There is an ending, but no. After a chuckle the narrator tells us he has no idea how it ends.

Ostensibly, the story is told by the off-screen narrator, of a hunting party of aboriginal men, who make ten bark canoes and go hunting and gathering in the swamp. Over that period in the story, a wise man tells a story to his impatient much younger brother. That “inner” story shifts to colour. It is supposed to be in a time in between creation and the full solidifying of men on earth. So the characters in the inner story are played by the folks in the outer one, and the main threads are folded together: a matter of the young man’s desire for the older brother’s youngest wife.

But that is the merest of threads. We are told that the story is a tree. We literally see that tree shorn of bark and made into simple canoes. We literally see our hunters — in both stories — camping in trees. The story seems to ramble. There is sorcery, mystery, charmed turds. There is revenge, jokes, anthropology. Its all of a context. A point of all this is that there cannot be a point in the western sense. There isn’t a linear narrative here with a message. There is a walkabout through a storyspace.

The very first event we see tells us this in a remarkable way. Our ten men are walking single file and the last man halts the party. He refuses to be last, he says, because someone is farting. The line is consequently reshuffled. It is a gentle device, one that sets the magic for what “follows,” a non-linear shuffle.

The joke at the end has the same form. The last one (the youngest wife) is not how the thing ends.

The entire production, we are told, uses aboriginal talent exclusively.

You want to know the narrative power of carefully folded (meaning here: intuitively structured) narrative? See this.

Posted in 2009

Ted’s Evaluation — 3 of 3: Worth watching.

No Comments