A team of explorers discover a clue to the origins of mankind on Earth, leading them on a journey to the darkest corners of the universe. There, they must fight a terrifying battle to save the future of the human race.

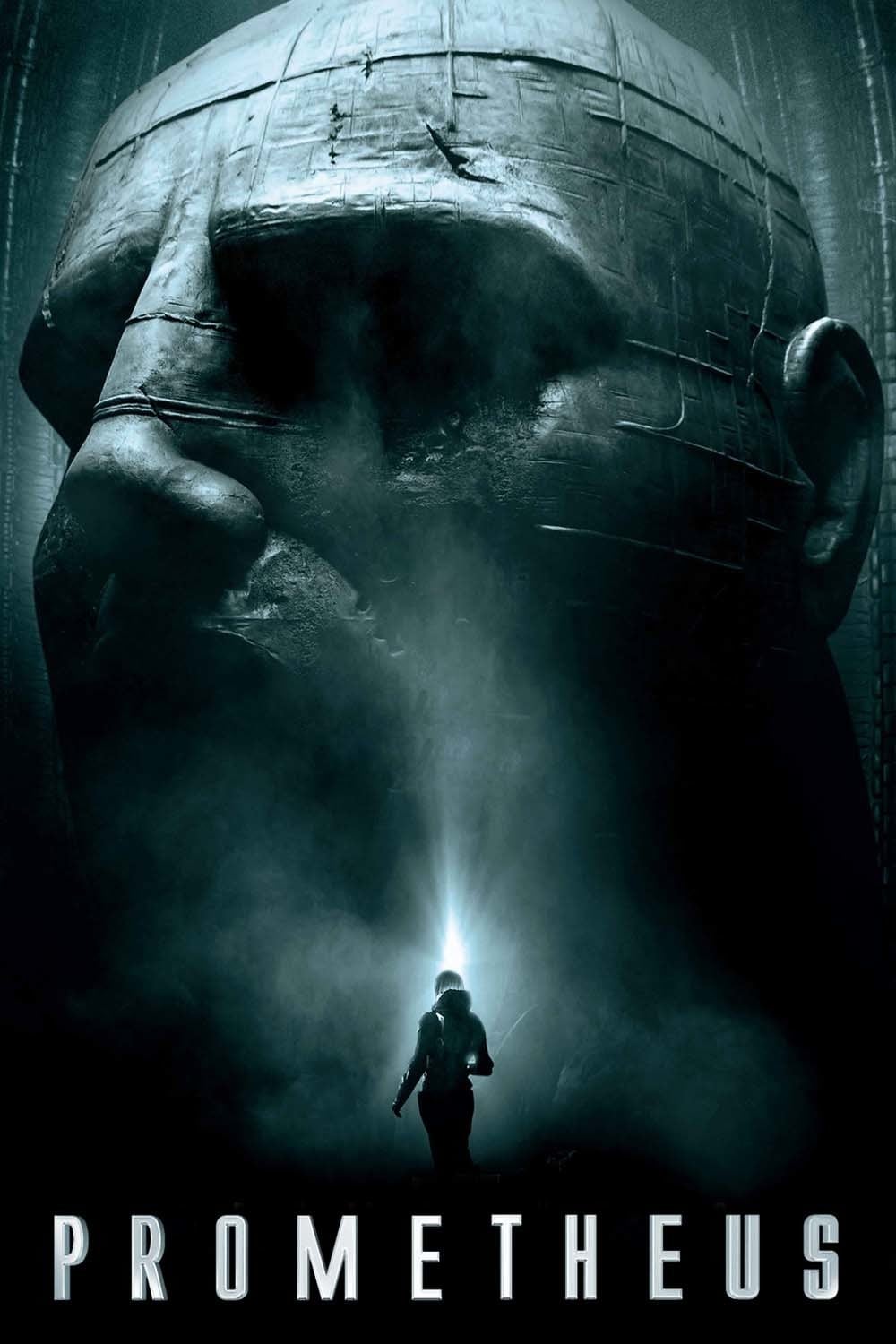

29 Jun Prometheus (2012)

Snowcrash

It seems all the writing about this film is about the story, how it doesn’t hold your hand and what religious metaphors are exploited. Well, that matters a bit because it elevates the thing out of the ordinary package. But a much more interesting way to think of this film is in terms of particles – how they build images and story elements.

There are many remarkable instances.

Chronologically first, we have the prologue to this prologue, a small film made independently of all else, and farmed out to dimensional experimentalists WETA. It is unlike anything that follows in many ways: nobility, flight of the camera, a blending of scale from planet to gene. There is only one element that carries over, and it is the notion of dust-sized particle. This forms the cinematic base of all else that follows.

If you have not seen the film, an alien ‘Engineer’ ingests some nanosludge, and it breaks his body into trillions of particles that interestingly swarm as a group and each transform microscopically. This occurs next to a massive waterfall, a real place in Iceland. But it has extra renderings later in the scene: a mass of coherent froth and a swirling family of clouds.

The nanoagents swirl with (slightly more) energy than nature’s vortices, and BANG, we have our main cinematic device. There is a story of sorts that this kicks off, and of course most people gnaw at that. Ridley wisely gives us only particles of that story, bits that leave a lot unexplained.

We’ll see this particle notion many times, this particle as image notion. We’ll see it first in the ordinary holographic display in the spaceship where an artificial man (after the fashion of Bladerunner’s replicants) spies on a naive female scientist’s dreams. (The basic vocabulary for cinematic holograms was set in the first Star Wars, and like so much in movie-land, we stick with it whether it makes sense or not. It is a mix of glitter, snow and image — particles.)

We see it in both sides of the technology, human and engineer. The humans have an extraordinary mapping/visualisation technology that displays using this fog/glitter particle imaging. The engineers have inexplicably made holograms of their actions that the replicant can replay. There are two of these, both extraordinary.

The first is handled in a way that only Scott could: he establishes a definition of space in ordinary, claustrophobic caves that all of a sudden is filled with these glittering particles which organise to give us a movie — a three d movie. We watch them watching it.

The second is so grand it challenges even Malick’s recent masterpiece. This is a swarm of white particles that organise to give is the most elaborate and thrilling orrery in films. It serves the plot to tell us (some will explain) about engineers, seeding and planned destruction. But for me, it is a sort of triumph of the white nanoparticles over the black — of coherent vision over dreaming monsters.

Think I am reading two much of this? Consider the two actual films within. One is a hologram of the sponsor, explaining the purpose of the voyage. It is cleaner than the others, but still based on this fine glitter. See how the effects have the glitter move to form the images — as opposed to just being suspended fog on which an image is projected?

The other film here is an actual film, “Lawrence of Arabia,” who our replicant emulates. That movie was the first to photograph sand as a self-organising society — one which defined an alternative cosmos to Lawrence. (The later “Woman in the Dunes” would elaborate on this.) Incidentally, it looked to me as if that inner film had been processed to be 3d.

This is the kind of thing Scott knows how to do, subtle and powerful. Look even at the one effect that was clearly added by funders to jazz up a section of the story. Our explorers race back to the ship to beat a storm of particles. This is an age old device, boring. The particles must be presented as benign because the planet (in most interpretations) has no consciousness. But even there, the particles swarm according to the patterns and vocabulary of that first segment.

Genius.

Posted in 2012

Ted’s Evaluation — 3 of 3: Worth watching.

No Comments