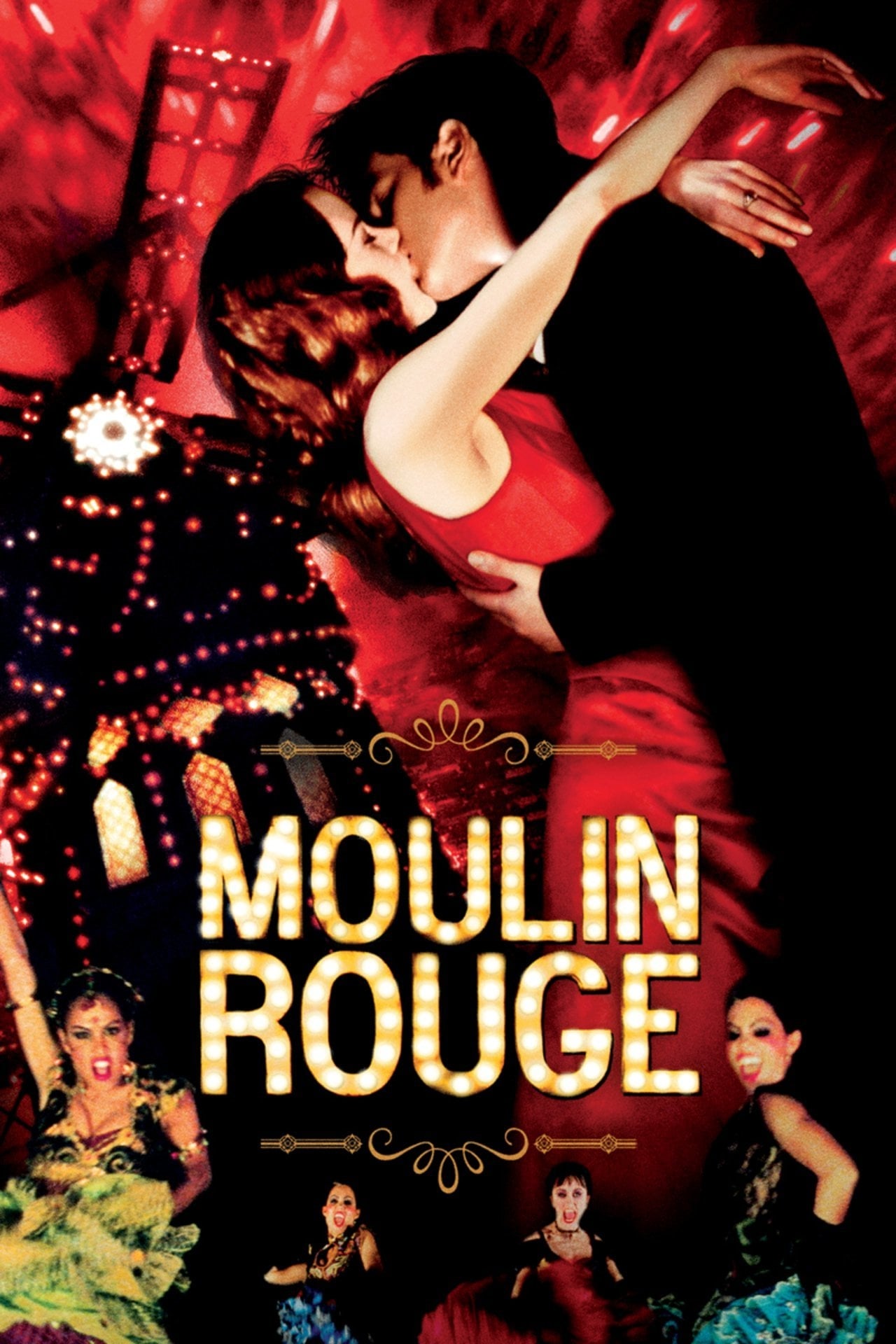

A celebration of love and creative inspiration takes place in the infamous, gaudy and glamorous Parisian nightclub, at the cusp of the 20th century. A young poet, who is plunged into the heady world of Moulin Rouge, begins a passionate affair with the club's most notorious and beautiful star.

21 May Moulin Rouge! (2001)

Glorious Absinthe Prostitution

This film is crafted of many common narrative elements:

- The rich cad versus the poor lad for the girl (with the conceit that love is unavailable to the wealthy ‘unreal’ class)

- The girl who must renounce her love to save her lover (only to lose her own life)

- The notion of players as prostitutes (here bohemian dadaists)

- The setting of a play within a play (with the everpresent driver that the show must go on)

- The extended bracketing (the opening/closing curtain, then the open/closing whiteface observer of the ‘mill,’ then the retrospective narrator writing what we see, then the initiation of the absinthe vision, all before the inner play — and that inner play has yet another level: performers in an Indian court — who are doing a song about a song)

It also uses an ordinary convention of embedding songs in the action. Though one must note that absinthe hallucinations are intrinsically musical and similarly embedded. (Don’t try this at home: thujone, the active ingredient in absinthe is so pernicious that is the only drug that has been successfully outlawed in the civil world. Think about that. Then imagine an absinthe bar on every corner and in every Parisian artist’s life 100 years back.)

Having mentioned all the ordinary elements, this film is the most fun I ever remember having in front of a screen. Everything to the smallest element is coordinated to be a single, transporting vision. And what a vision! The camera has character here — it is a performer, it dances, laughs, cries — it is detached voyeur, then intimate partner. Everything is so original in vision, and so coherent it amazes. This is close to scifi — it conveys us to an alternative not-quite-real world we can barely reach.

The actors play to a knowing camera-audience. There is an amazing sequence in the elephant when the Duke first interrupts the writer and the inner play’s cast makes up and acts out the play in front of us. This of course includes self-reference of the current situation. We are so swept up in the exuberance that we lose our place. What layer were we in?

(A talking sitar that can tell no lie? A narcoleptic Argentinian? The dadaist Latrec as the story’s stable centre? A connubial elephant? — Glorious prostitution.)

The layer shuffling happens again with a more edgy and sinister tone with a Tango to Sting overlain with other music and emotions: the ‘real’ action with Satine and the Duke. We lose our detachment again because the layers of self-reference are juggled. The finale echos this.

Nicole does the best job of her career. She is so totally open here one worries for her — I suppose this is the Emily Watson effect.

Baz is now among my top three directors. This is a near perfect film in execution. The one flaw comes from that perfection. Broadbent is a perfect Zidler. But he has played this same role before — recently, and in a similarly nested play: ‘Topsy Turvey’. It takes a small chip away from the originality if the film.

See this. See it twice in a row, the second time for the absinthe, and allow yourself to be ravished deeper than you knew you existed visually.

Posted in 2001

Ted’s Evaluation — 4 of 3: Every cineliterate person should experience this.

This is an extension posted in 2023 to the original film comment of 2001, more than 20 years ago.

I have just seen the stage show in Brisbane. Under normal circumstances, a theatrical event, even a transformative one would go into my soul directly. But here it is accompanied by a prior transformative film experience whose effects it builds on. So even though my first encounter with the film was decades ago, it awakened and rebonded the initial emotional network from that film: my life against the winds of a world unfriendly to passion.

The emotional fabric is not about the people, but the environments that compete.

On the negative side, we have death — that constant exit, through which we either fly sated with life or are dragged disappointed. And we have simply the way that unfairness deposits itself in people to obstruct us.

On the plus side, we have the raw energies of both self and friends. On this plus side, love is conflated with a Bohemian ideal and the comradeship that induces.

The magic of the story is that art and love are conflated, with performance in each separated from both.

Okay, so much for the basic components. The way this is delivered is what makes it work. In the film, the songs carry all the constructive energy. They have power because most of them are familiar and provoke us into the innumerable pasts when we earlier heard them. This, at least for me, evoked emotive extremes unlike any other theatrical device. Love is as much about recalled memory as it is a yearning.

Separately, in the film, the obstructive forces are conveyed by cinematic structures via a mix of spatial and temporal provocations, but heavily weighted on the management of time (the editing), with space (the sets, movement, and camera) in support.

This mix in the film worked for me. I do not think I am much different from many in this regard, other than noticing it — in part enabled by the explicit folding of a performance in the performance.

Now on stage, they take these very same elements and are able to ratchet up every effect. Songs conveyed in real life by talented performers will always produce the most emotive experience. They changed the songs with a fireworks pattern of new content, surprising and amusing. Because we are actually listening, and constantly surprised, the connection is greater than any I have felt since Argerich’s Chopin. (She is who Baz referenced with his narcoleptic Argentinian, and if you have never heard her, you must while you are still open.)

That leaves how they evoked what Baz did with cinema. Here, they could switch the time-space balance of cinema to having space dominant. I have never experienced anything like the orchestration of form I had in those couple hours. It was masterful enough for me to want to use it in art that I now must, must produce.

Here is an example: In the film Satine dies within the context of film and theatre death scenes, with drama and anguish. We count on the actors and not any text or staging — not even any music. This is one zone in the film where scant experimentation occurs. We have distance before and after but not in the death.

The show has a simple event that must have been the result of much experimentation and work. She dies and the cast comes from some random assembly to a surrounding flower that envelopes her briefly then she gracefully is absorbed when carried off. The way the cast moves to form this flower is overpowering. It takes all but ten seconds, but is so masterful I would have been happy with it alone. (I was in the balcony and recommend that.)

So, if you carry or anticipate such memories, I recommend the film and the show. The audacity by itself is contagious even if that’s all you want.

Things I might have changed however…

In the film, Satine is a performer at heart and a sex object incidentally. Her lover and her performance enabled by the lover overlay and reinforce, so the drive to continue is a consummation of both. In the show however, she is a sex worker pressured to save the company and her friends.

Harold in the film is a doting father figure, perhaps under her charms and worried about choices. In the show, he is gay, selfish and the key bad guy. Without his pressure to sell her body, Satine would be free to run.

In the film, Satine is betrayed by Nina, hungry herself to perform, but here Nina’s sisterly support has its own scene, and the rat is a male.

The inner play is almost absent which is a real shame. ‘Spectacular Spectacular’ in the film had manifolded agency, apart from the best jokes in the film.

Instead of a young French writer intent on writing the greatest love story ever told — our framing narrator — we have a callow American songwriter from the midwest. The film has Christian as a writer; his art is the love story we see, so we are literally in the shape of his soul as he experienced it. That’s lost here. Christian is a songwriter, and that changes the equation deeply and threw me off a bit. It means the experience is not a retrospective account, but immersively lived to evaporate instantly. That’s the way it feels now in my life, so I accept the judgement.

But the biggest loss I think is Toulouse-Lautrec’s character. The film has him as an endearing artist with deep ideals driven by a thujone-maintained dream world in which the four ideals insist on life as performance. In the show, he is more of an obnoxious Marxist with a stunted love of Satine, hobbled he feels by his physical deformity. I surely would not have made that choice because one of the possible worlds in the original is that he hallucinates the film. Or conspires with Christian to do so in an Absinthe revelry.

Also missing is the vaginal elephant interior.

But hey, if you saw the film, and it mattered to you, this will build on that and make you young again. Do it, then perform.

Posted in 2023

No Comments