Newly elected President Nelson Mandela knows his nation remains racially and economically divided in the wake of apartheid. Believing he can bring his people together through the universal language of sport, Mandela rallies South Africa's rugby team as they make their historic run to the 1995 Rugby World Cup Championship match.

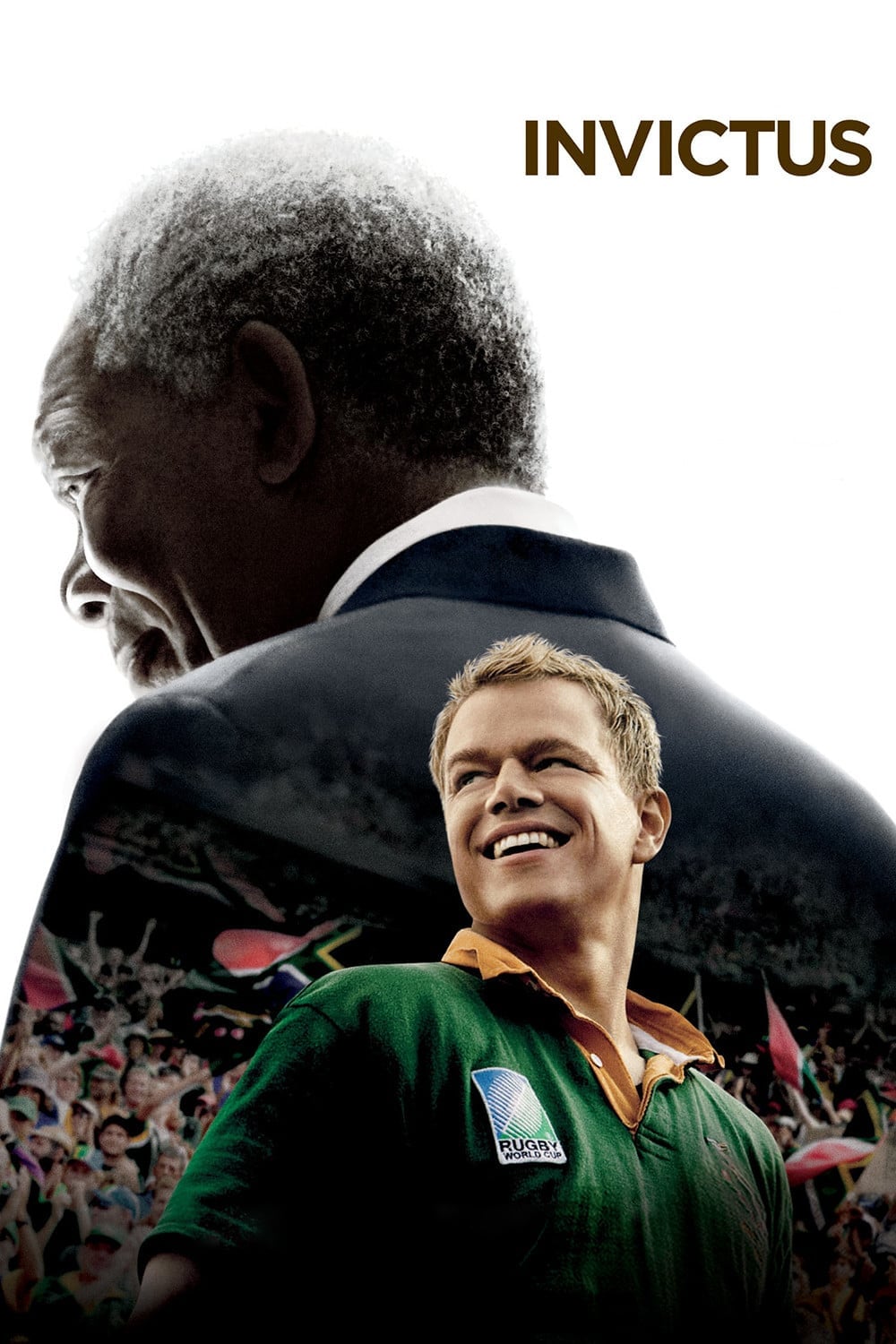

19 Jan Invictus (2009)

Locker Room Lockup

To my mind, this is less about South Africa, sport and Mandela than about another man.

Oh, the drama was really there. It doesn’t matter that it was not as significant in uniting a nation as depicted. How could it be? How could it?

But the dramatic form is there because it works. We like to show the sweep of the large by embossing on an individual. Here at least we don’t have love. And we like to illustrate a personal struggle by showing masses in huge movement. Masses and mass excitement are cinematic, and human internals cannot be. So we show internal struggle by external means.

What I celebrate is another man, Clint Eastwood. Now here is a man well past the time he could relax, making significant films. This is not complex like (XXX that Boston movie), nor as cheaply mawkish as “Million Dollar Baby.” It is in between. But it is — if I recall — the first time Clint has shown mass movement. Here he uses Morgan Freeman in ways that Morgan has a hard time cheapening the thing.

Photographing moving team sports like football, soccer and basketball is something of a challenge. You have to make decisions about what role the camera plays. Dance is a similar challenge, but you have more flexibility because the tradition in theatre is to break the walls and engage. In sport, the barrier between player and watcher is sacrosanct. The drama depends on you investing in the game; the fiction that the players represent you is tangible.

But it equally depends on you being remote, whether in a stadium or in an upholstered chair in your home. That distance makes the business work. It allows representation without inclusion, because the viewer gets the pleasure of having someone else do his work for him. It has to be explicit that it is someone else.

So the camera cannot take the viewer into the game as a participant. It has to always be a watcher. But how to do so, staying within the carefully evolved confines of watcherdom and still give us some greater immediacy? Eastwood finds a balance. He relies a bit too much on the camera on the ground, looking into the locked players for me. But he strikes a better balance than say Oliver Stone does in “Any Given Sunday,” which is basically a war movie without death.

Eastwood. Building a legacy, one small but well crafted film at a time. Who among us ever suspected that this fellow, with no film school, no real musical training, would become one of our most practiced directors and film musicians.

Posted in 2010

Ted’s Evaluation — 3 of 3: Worth watching.

No Comments