During China's Warring States period, a district prefect arrives at the palace of Qin Shi Huang, claiming to have killed the three assassins who had made an attempt on the king's life three years ago.

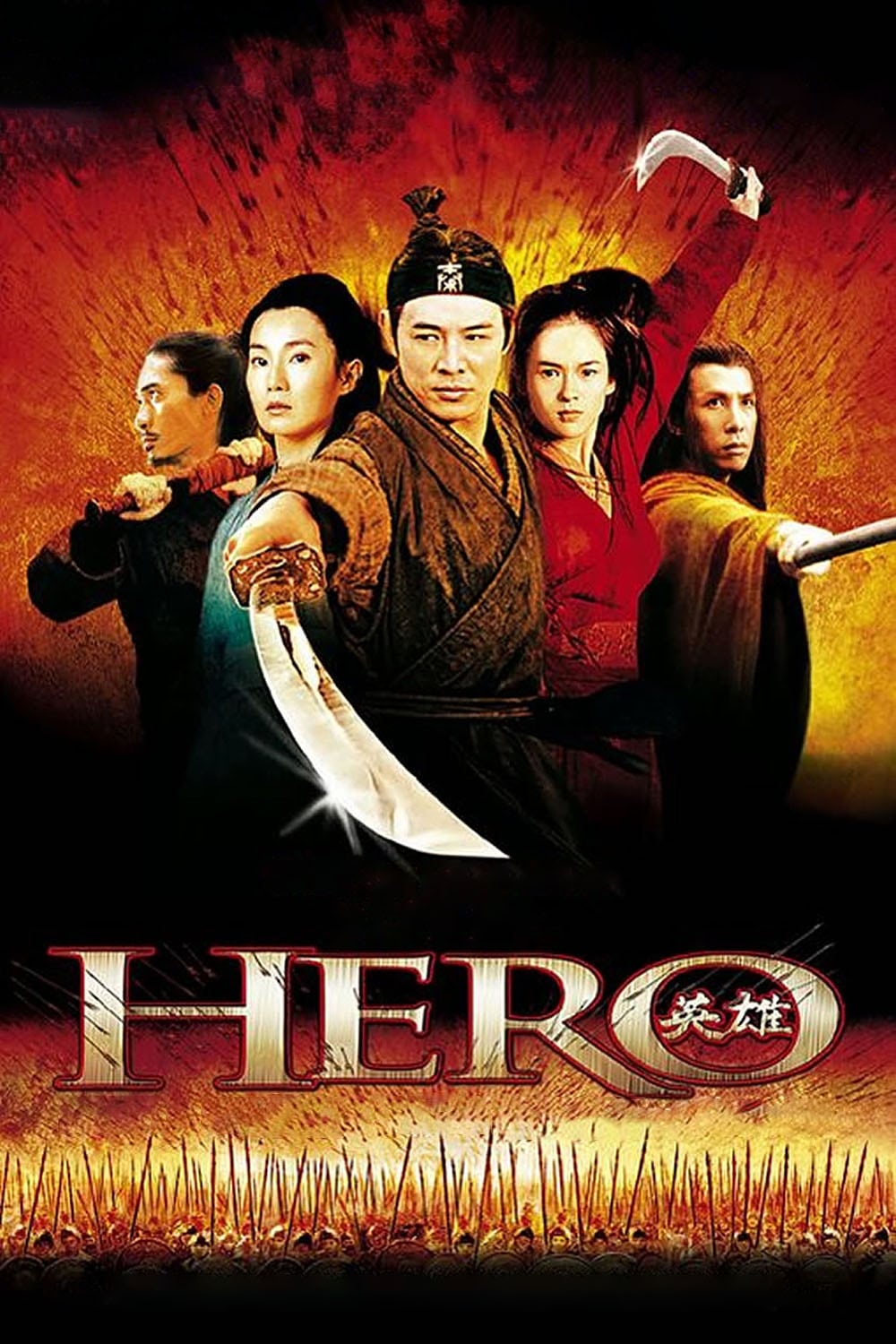

23 Oct Hero (2002)

Space

Two things interesting about this project. First, the sad news, at least for the Chinese, that the Japanese have finally won. This is a Japanese film in all important respects: the theming by lush colour, the rather modern notion of benevolent conquest (genuinely originating in the Persians but only used since as justification for selfish empire, specifically in this case Japanese conquest — and adopted by the Chinese only since the war) and of course the wholesale swallowing of Kurosawa.

Kurosawa is here obviously in the story: it is half “Rashomon” and half “Ran.” But more important is Kurosawa’s theory of film as a device to capture space. As with Parisian impressionist painters, the thing painted is not the point. It provides an origin only; the painting is about all the magical things that happen in the space between the subject and the viewers eye. The paintings, and Kurosawa’s films are about that space.

Kurosawa invented the technique of shooting from very far away with a telephoto so as to flatten space, and at the same time creating (usually three) layers of space. Often, he would engage the space directly.

This masterful film is obsessive about the point and may be the most lush swim in dimensional space you are likely to find with the technology we have. Every shot is oriented around not the action, but the space that contains the action. Falling water, dust, lots of blown fabric and hair, feathers, arrows, even book tablets and those leaves! With lots of bamboo screens, all these are used to show the space, plus the usual fantastic mountains, clouds and forests — even at the end the Great Wall and of course the moving waves of soldiers and courtiers.

The matter is not lost in the copious allusions to mental space: the game of Go, music, calligraphy, politics, and love. All these are defined, exercised and conflated with one another in terms of space and the intrigue of space with a little more effort in the latter items on the list. Then, waving lamps are used to make “murderous intent” spatial.

Unlike “Crouching Tiger” which this resembles not at all, the camera is static, not dancing. Where Lee emphasised the ballet of the fight by engaging his camera, Zhang stands back in the space. Where Lee conceives fights not among the participants but their masters, Zhang shows us not the fights, but the battles among the true worlds of the fights — the worlds of different colours.

What we see could be the imaged Go game, or the imaged fight within it, or the imaged story Nameless tells, or the one the King tells and on and on with nestings of imaginations.

Every nation creates their own movie to explain themselves. We in the US seem to like more militarist stuff. Except for the thuggish motive (my war for my kind of peace), we would do well to have stories about stories like this one through four layers until they reflect back on the origin. Complex story space in rich real space.

If you are going to see this, you really must see “In the Mood for Love,” which features Broken Sword and Flying Snow in something of the same relationship they have here. It is one of the best films ever made and truly spatial in a purely Chinese manner. It will completely transform your enjoyment of this.

Posted in 2004

Ted’s Evaluation — 3 of 3: Worth watching.

No Comments