A fearless Secret Service agent will stop at nothing to bring down the counterfeiter who killed his partner.

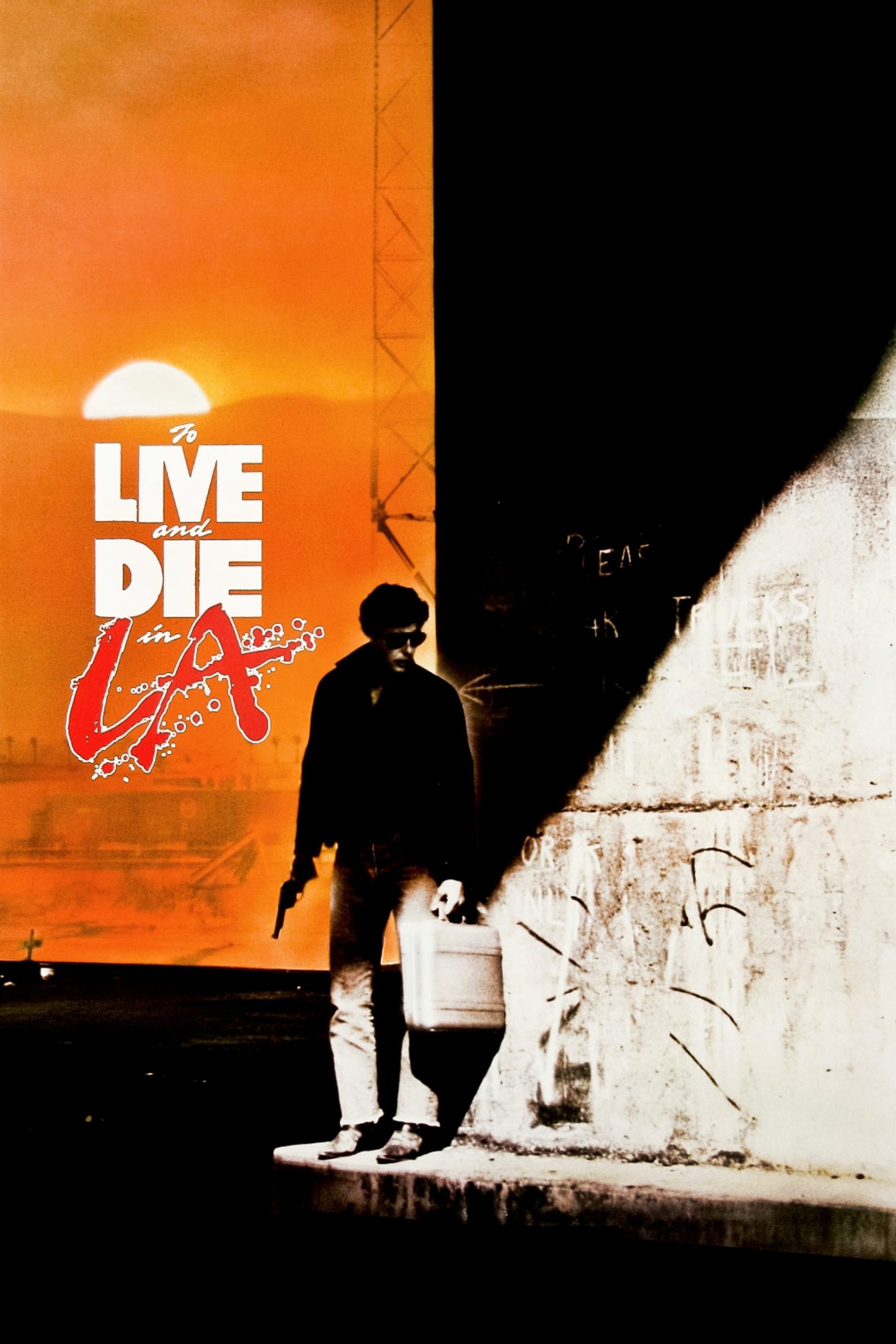

22 Feb To Live and Die in L.A. (1985)

Two Women

Making a story that connects is a balancing act that rarely succeeds. You have to use the machinery of storytelling to engage, taking advantage of the power of the devices you select. But at the same time, you have to conceal that machinery. This is a contract between filmmaker and viewer. Often the qualities are relatively intangible, like the way a conversation is visually framed or a line paced. Or an erotic scene seductively constructed.

But sometimes the machinery is more overt. Many of Hitchcock‘s masterpieces don’t work for me now because the stage is obvious many older action films don’t grab now because the action effects are clearly bogus.

Here is a film that once was terrific. The car chase wasn’t a collection of clichés, and was thrilling. The bad boy cops as unglamorous thugs was unusual. The various analogies of counterfeit were arguably artistic. The score was mainstream and not at all distracting. None of this is true now, and this allows us to notice other details of the craft.

There is a seriously unimaginative staging of conversations whose only purpose is to explain to us. The dialog is stilted and silly in places, as if an assistant wrote right before shooting. Many of the actors seem not to have been given coherent characters.

And yet, within this story, one plot device has mellowed. The overall anchor concepts in the film revolve around duals and fakes. Two of this and that, real and not, compliant and not. Entanglements between pairs and tensions. We have two cops, newly assigned buddies and the main focus is on them. Ho hum. In the background are two women. Their characters are not trivial, and over time these have become more incisive and for me overtook the entire movie in spite of testosterone-driven noise.

One is the counterfeiter‘s girlfriend and partner. Tall, thin, explosive red hair and cool execution of plans, she is played by Mickey Rourke‘s then wife, when image and roles mattered to him before drugs. She is presented as the obsessive object of the counterfeiter, who is truly an artist driven to paint her. He creates impressive images of her that aren’t quite up to her presentation of self, so he equally obsessively burns them. His anchor in life is her — not her but a fabrication of a woman she is able to sustain.

She, we find, is a performance artist and we see here a few times in this mode: extreme abstraction in staging, makeup, movement, lighting. The effect is powerful, this folded acting a woman within the acting of a woman. It is one of the best roles of that decade, submerged.

Another woman: thin, always on the verge of panic. A victim. She works as an arranger in a strip club. A felon for what should be a minor sex offense. She is on parole and is being exploited by our bad cop for both sex and information. The sex is coerced. The woman is his reluctant slave, and yet the connection is deeper and more genuine in her desperation than anything our cool redhead can muster. The end of the movie — a rather overlong coda — has our cold conniver driving off with an even more abstract version of her pretense at being a female. The slave? She simply is an inheritance for the next guy.

A movie that has decomposed a bit, allowing this inner muscle of taught/taut womanness to be revealed.

Posted in 2011

Ted’s Evaluation — 2 of 3: Has some interesting elements.

No Comments