An adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald's Long Island-set novel, where Midwesterner Nick Carraway is lured into the lavish world of his neighbor, Jay Gatsby. Soon enough, however, Carraway will see through the cracks of Gatsby's nouveau riche existence, where obsession, madness, and tragedy await.

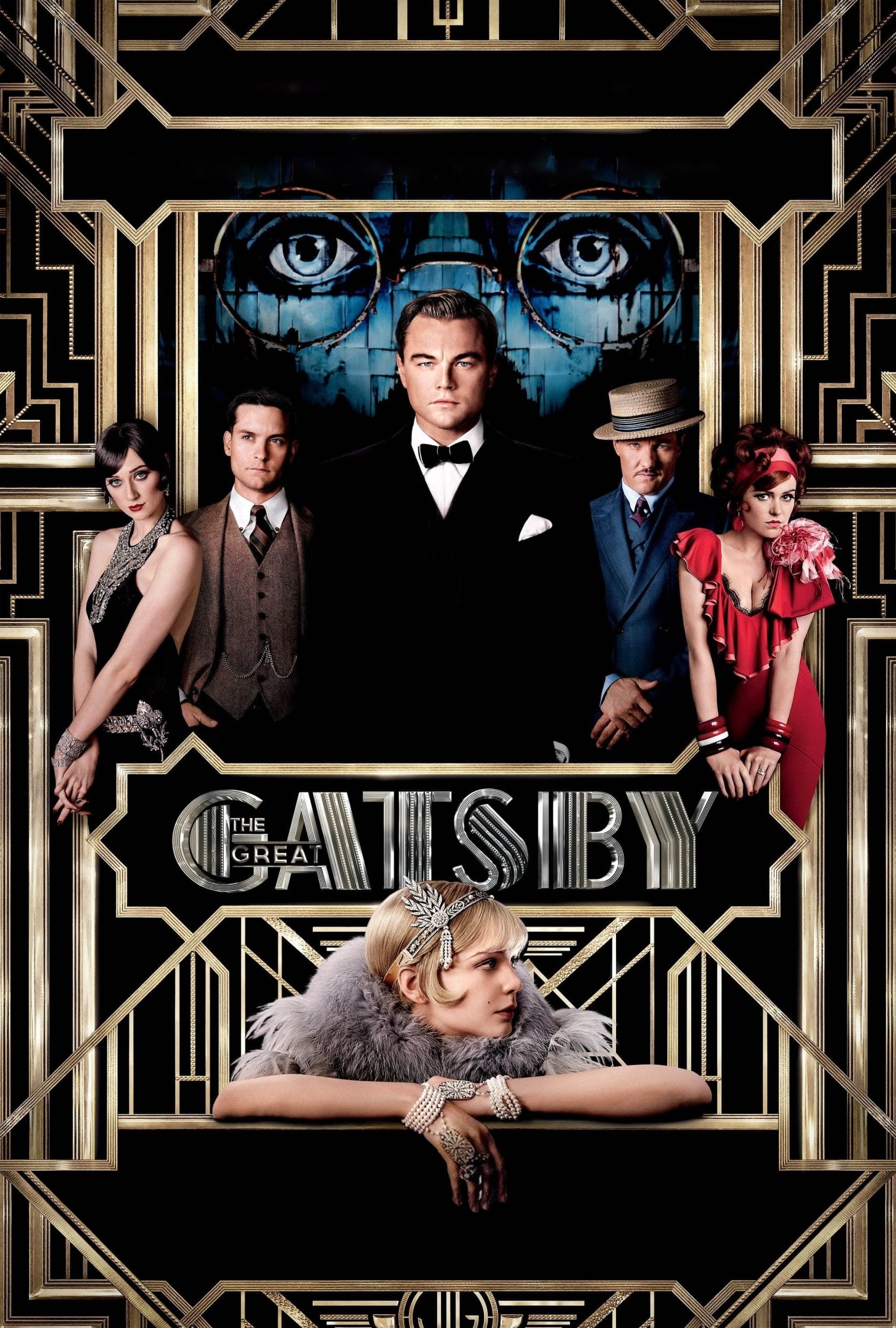

06 Feb The Great Gatsby (2013)

Moulin Green

When I saw Moulin Rouge,’ I knew that life would change, because film would have an added mainstream vocabulary. We would embrace it and adjust our dreams and intuitions. And indeed we have had Nolan ascendant. Even TeeVee has shifted.

Oddly, after that film, Lurhmann himself went off on a different experiment, trying to exploit openness rather than constraints of space and view. That failed interestingly. Now we are back at the ‘Moulin Rouge’; form again.

That means that we get layers of observation, not necessarily nested. We get shifts in narration that have related cinematic devices, spaces or camera movement. And all of this will be relatively invisible so a mainstream viewer will think she is watching a regular movie.

The novel sets this up well. Everyone in that written world is living a fragile story, partially self-created. Some notions in the story have become less powerful since the time of writing, for instance we have a different notion of the damage carried by soldiers returning from war. But the impending collapse of identity narrative is much sharper today than in Fitzgerald's time, at least the ones we see, based on our knowledge of and wishes about the the collapse of class privilege.

What characterises the American novel is unsettling narration. In this case, each of the main four charm us into trust, only to have that trust dissolve. The movie adds two new things to the story. The first is a rather heavy framing device where the book we see is written. This gives some purchase for the voice over narration and allows slippery shifts between inside and outside the main thread.

The second addition is the use of the romance movie genre. It pulls on the film in ways not available to readers of the novel. When we see a date movie, we willingly enter what we know to be a desirable but unrealistic world. We see these with our lover, hoping to stitch elusive unachievable remnants into our own pairing.

I’d say that Lurhmann exploits these masterfully in teasing us into one precarious position after another as partygoer.

The story itself revolves around two scenes. The first is when Gatsby arranges to meet Daisy for tea. This is where reality first threatens the elaborate story Gatsby has woven. Decaprio sought the role for the tensions he could bring to this dynamic. It is introduced here and he surely places the problem squarely in my heart.

The second scene is when Daisy has to act to consummate what we accept until then as a delicious love story. The two scenes go together with the spring set in the first sprung in the second. We need a profound actress to pull this off. Someone stronger even than Leo. Our actress here destroys the film with her weakness as actor and character. Her choice in the book is one of strength, choosing (local) truth over Gatsby’s fantasy. Not here.

Two other weaknesses. The first is that in the book not only are our main characters untrusted narrators over their own lives, but Nick is an untrusted narrator. He is in love with Daisy. He is the penniless war veteran. He is the one tempted by shady financial deals in order to win a love. The book leaves the possibility that Gatsby is his invention from drinking and intersheet fantasy.

The second weakness is that Luhrmann is a master of nested narrative, but he doesn’t know how to change the presentation of inner layers. So for instance, we see, actually see Gatsby save a drunk millionaire and it is presented in the same manner as everything else. There is no need for this, and Nolan does so much better.

But never mind. We come for the cinema. We come to be harmlessly tricked. This doesn’t change the world like the red film did. Lets call this the green one. If he pulls a Kieslowski, there will be an orange one. Speaking of Kieslowski, I'm a fan of Lurhmann when he collaborates with structureman Craig Pearce. They had a lot of freedom in Moulin Rouge and used it to great advantage. The thing turns itself inside out several times and is vastly more complex than ‘Inception’

Where Nolan has wife as visual anchor and brother for narrative structure, Luhrmann has a similar setup. Both Nolan and Lurhmann produce visual worlds with some striking features, but the key thing is that they are internally coherent. I’ve become a believer in the power of a sexually engaged collaborator for this. The visual coherence helps with the overlay of the narrative structure; the more reliable the visual world is, the more possibility we have for non- linear elements in the narrative world.

Fitzgerald's novel is almost tailor made for this approach. Many who read it see only the society therein and the associated metaphors for a world adrift, buffeted by collective urges. Of course that has power. But the more interesting thing about the novel is the devious slipperiness of the narration.

Posted in 2013

Ted’s Evaluation — 3 of 3: Worth watching.

No Comments