Late in the 1500s, an aging tea master teaches the way of tea to a headstrong Shogun. Through force of will and courageous fighting, Hideyoshi becomes Japan’s most powerful warlord, unifying the country.

20 Sep Rikyu (1989)

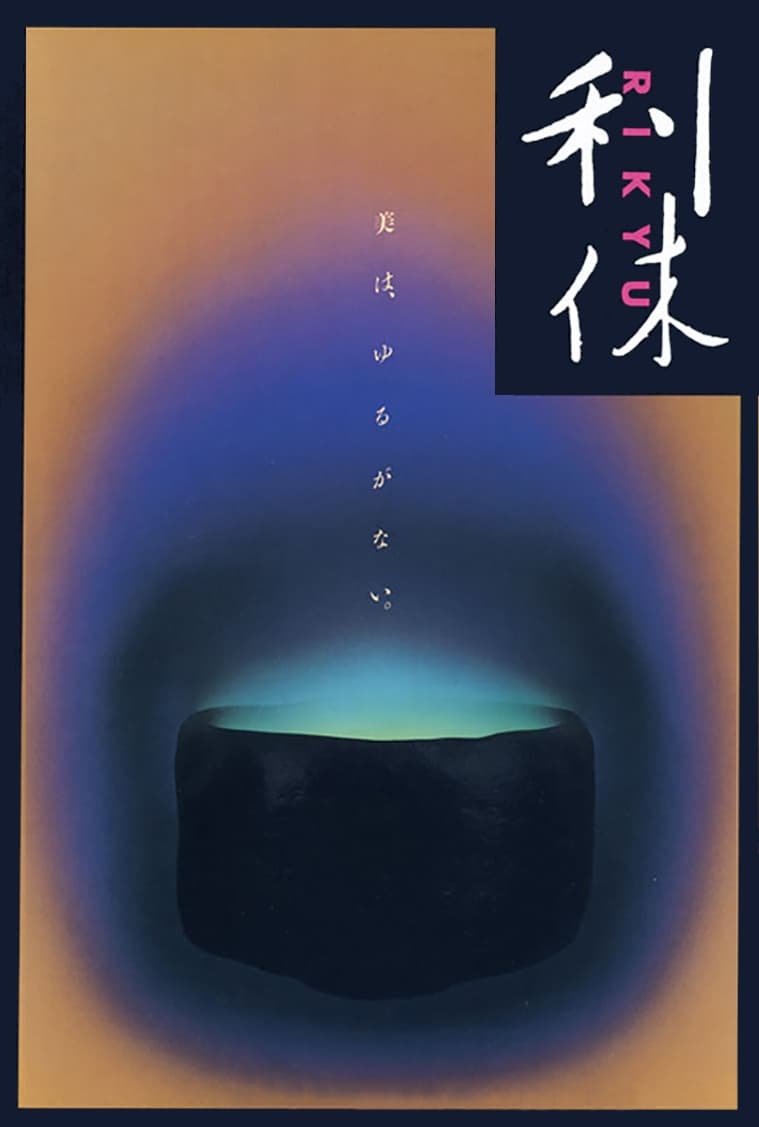

Broken Black Bowl

Film can be something thinly exploited for pleasure, or it can serve as tool for living. Many films span the two existences, but not this one. If you are looking for a way to amusingly spend time, this isn’t for you. But if you want something that is intensely lush and explicitly meditative, is zen in subject but a polemic in form, this could be important.

First a warning, the Slingshot DVD is a crime against humanity — it has taken something lush and wonderful and trampled repeatedly on it. The colours are washed out; the transfer is fuzzy, the sound loud and distorted, the subtitles often unreadable. Its apparent pan and scan is not obviously offensive, but the very idea of changing these compositions is repellant. See it in a theatre if you can.

Film master Akira Kurosawa is Professor Hyakken Uchida in his later ‘Madadayo’ likewise floral master Hiroshi Teshigahara is tea master Rikyu in this film.

For background: Rikyu was an extremely important figure, one can almost say that he invented the core of what it means to be Japanese. He translated some rather abstract Shinto notions into a manner of relating to ordinary customs, objects and environments. At precisely the time that Shakespeare was doing something similar in inventing the modern human, thereby escaping medieval barriers, Rikyu was reshaping many of the same medieval barriers into noble form.

All film derives from the ‘Shakespearean’ influence, and it is the work of Teshigahara to re-form the principles of quiet engagement with the refined simple life with the folding an refoldings of self-awareness. So when he makes a film like this, it is much in the same vein as Tarkovksy’s masterwork : ‘Andrei Rublyov,’ a creator of (static) images who invented the soul of Russia. That is to say, Teshigahara is about reinventing us, and he is a trustworthy master on this voyage.

Most know that he heads the influential Sogetsu school of ikeban (the philosophy of expression in “floral” arranging and viewing). It takes previously staid notions of balance/imbalance (‘katachi’) into radical new, self-aware directions. It is not merely a matter of decorative style, instead an enfolding of western reflection into the meditative symmetries of what Rikyu spawned.

The story, bound by actual history, is rather simple and is unrolled in straightforward fashion. What is important here is the depiction of the master, and what it means to be a master. The plot turns on Rikyu’s unexpected and radical approach to arranging plum blossoms, which is the real offence against his vulgar ruler.

Yes, this is slow by western standards. Yes, the quality of the artefact is ruined, a broken bowl. But for students of life, this is worth looking into.

I only know two other of Teshigahara’s films; filmmaking is only annotative to his ikeban, and he makes few. But he makes them as if he were speaking, or moving. The first is the remarkable ‘Woman in the Dunes.’ The second I know is an examination of the architect Gaudi, a truly profound thinker — a master — who deserves to be ranked with Shakespeare and Rikyu. That film is ordinary in effect, but the ideas behind it are as powerful as those behind ‘Rikyu’.

Posted in 2003

Ted’s Evaluation — 2 of 3: Has some interesting elements.

No Comments