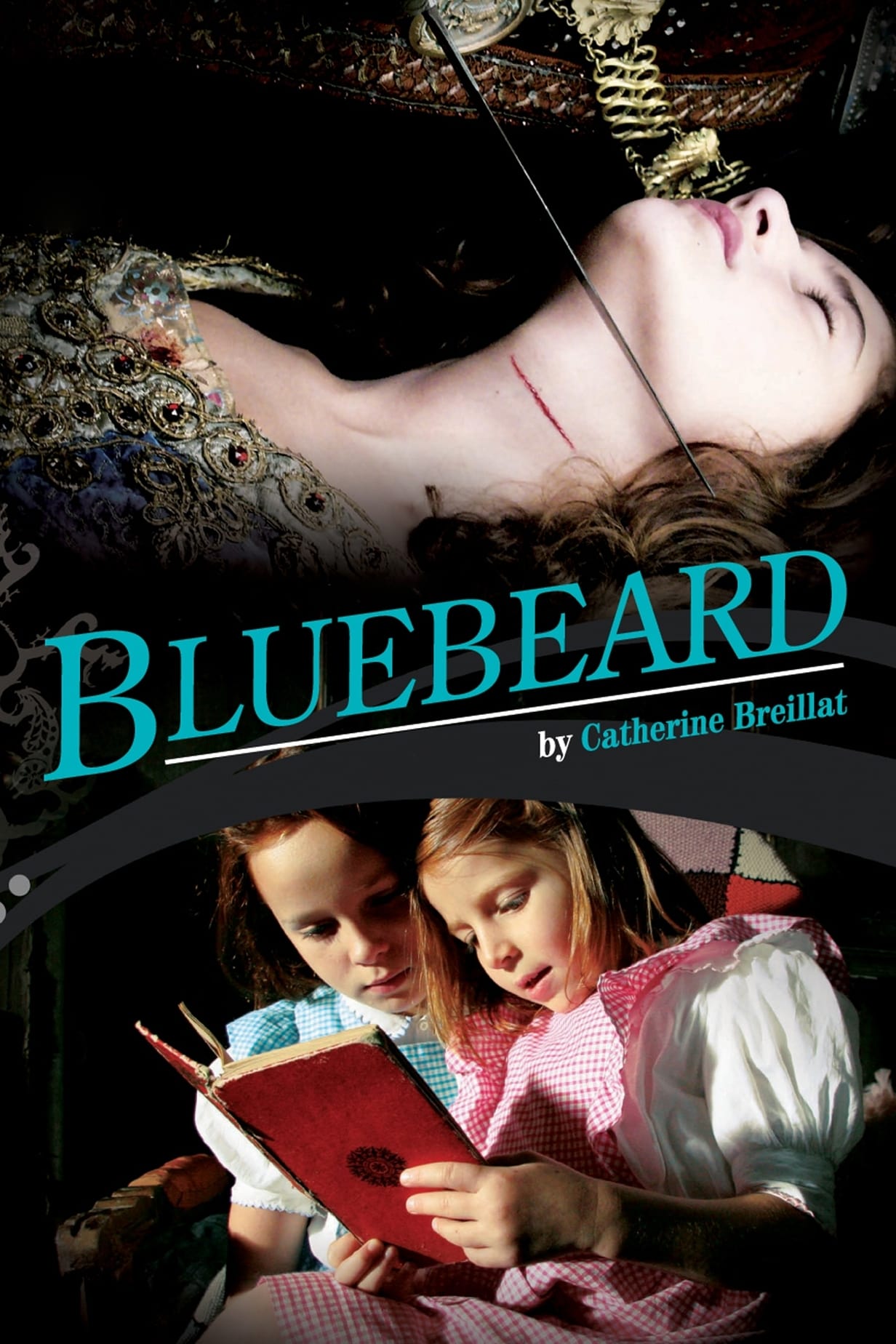

Anne (Daphné Baiwir) reads her younger sister, Marie-Catherine (Lola Créton), the story of Bluebeard. In 17th-century France, another set of sisters — also named Anne and Marie-Catherine — are left impoverished by their father's death. Marie-Catherine dreams of marrying into money, and soon falls for wealthy divorcé Bluebeard (Dominique Thomas). Grateful for the chance at a life of comfort, Marie-Catherine marries Bluebeard — in spite of rumors that he has made a hobby of murdering his wives.

01 Feb Bluebeard (2009)

Bresson’s Beast

It is a sad thing to see the tragedy unfold, that tragedy of growing weariness of life we have impressed on the story of the lost innocence of a girl.

There are three such stories here.

The least interesting is the ‘fairy tale’ itself: an innocent younger sister by fate ends up married. Her impression of her husband is stretched in her mind: he is huge, with appetite to match. Urges related to sex, which she has not yet felt, are mapped onto bloody murder. Her wedding night will be a death. The bridal chamber, accessed by a golden key, is a storehouse of dead women, all dripping fresh blood on the floor from under their nightgowns. Fears, fears. Unlike the typical Breillat, the man here is gentle and suffers. But like the rest of her work, it concerns the strangeness of sex as it barrels into young girl’s lives.

All of it is highly abstract, absurdly so.

Redhead note: our girl’s older and wiser sister is played by an extreme prototype redhead. When they get to the castle of grownups, they encounter an actual sexually active woman, and she is yet more extremely redheaded. There is an initial recognition and embrace.

This tale is wrapped in a second, set in Brellait’s childhood era. In this case, two sisters — younger than those in the tale — discover the book of the story. Much is made of the disparately between the two: the younger one is ‘more advanced’ and she lords it over her sister. When we see these two, peppered throughout, we see how profound is their ignorance of adult ways. As the inner story produces its gruesome end of an undeserved death, so does the outer story.

But there is the third story, the outer wrapper, the story of the filmmaker who we knew as a young woman. She made some films full of energy, richness, sexual imbalance and personal pain. Now she is a mature woman, and all the blood is gone. All we have left is lifeless metaphor.

Posted in 2011

Ted’s Evaluation — 2 of 3: Has some interesting elements.

No Comments